Dinosaur Supervisor

Ahora que todo mundo está de nuevo interesado con el tema de Jurassic Park, aquí hay una interesante nota que leí al respecto de esta secuela iniciada por Spielberg y que revolucionó los efectos especiales en el cine. La historia es sobre uno de los animadores de stop motion más famosos de antaño (Phil Tippett), que aprovechó el cambio de lo análogo a lo digital en el mundo de los efectos especiales (CGI) para obtener uno de los puestos mas envidiables que se han conocido en la industria del cine: “Supervisor de Dinosaurios”.

Me alegra pensar que lo nuevo siempre se alimenta de lo viejo…

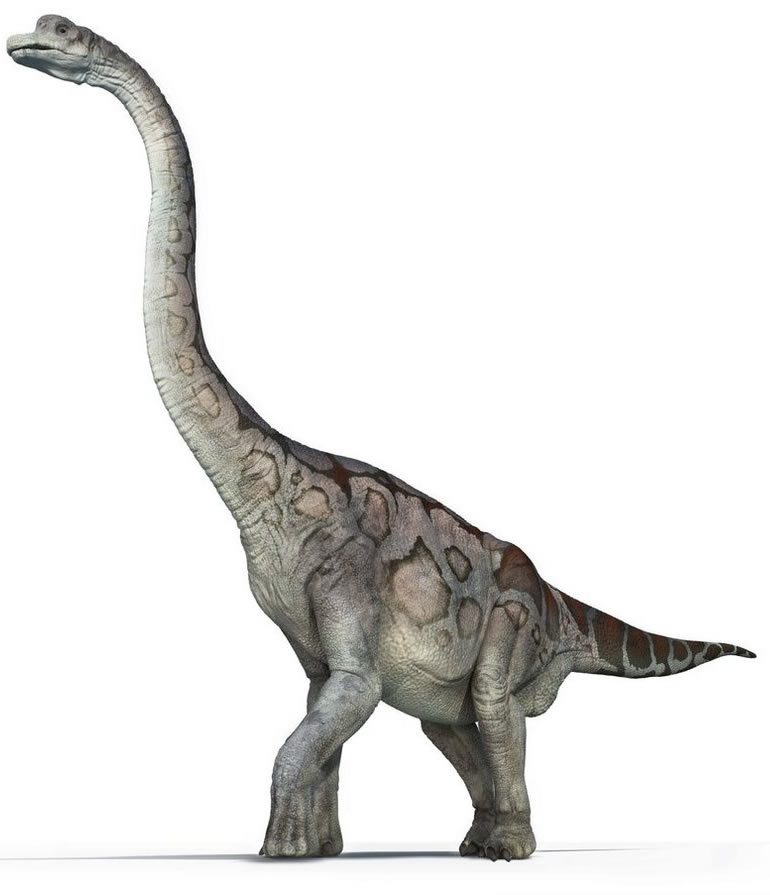

Spielberg assembled the Mount Rushmore of VFX — Stan Winston, Phil Tippett, Dennis Muren and Michael Lantieri — to bring dinosaurs to life for Universal Pictures’ adaptation of Michael Crichton’s book. The plan was to incorporate a blend of conventional techniques: full-scale mechanical dinos (like the T-rex at the paddock and the ailing triceratops) and high-speed miniatures (the running herds, many of the raptor shots).

At the time, Industrial Light and Magic was experimenting with computer-generated graphics, which it had used in the James Cameron films The Abyss and Terminator 2: Judgment Day. But CGI had only been used to make stylized liquid and metallic surfaces, not living, breathing creatures. Muren, who had been working with the technique at the Bay Area effects shop, suggested they give it a try, and created a short shot of T-rex running through a field.

“I’ve become extinct!” Tippett famously exclaimed, a line Spielberg liked so much he wrote it into an exchange between Drs. Alan Grant and Ian Malcolm…

But Tippett had learned an extraordinary amount about paleontology, the physicality of dinosaurs and the movements of animals for Jurassic Park and his previous dinosaur short films. Though the creatures’ bodies were being moved from his fingertips to computer screens, Tippett knew how they were supposed to look and behave. He had a new role: dinosaur supervisor…